Small-scale sculptures. The XX century. Origins

Russian style. (Рart two)

The Russian history's first sculptural images of the naked female body brought the glory to Sergey Timofeyevich Konenkov, the "Russian Rodin".

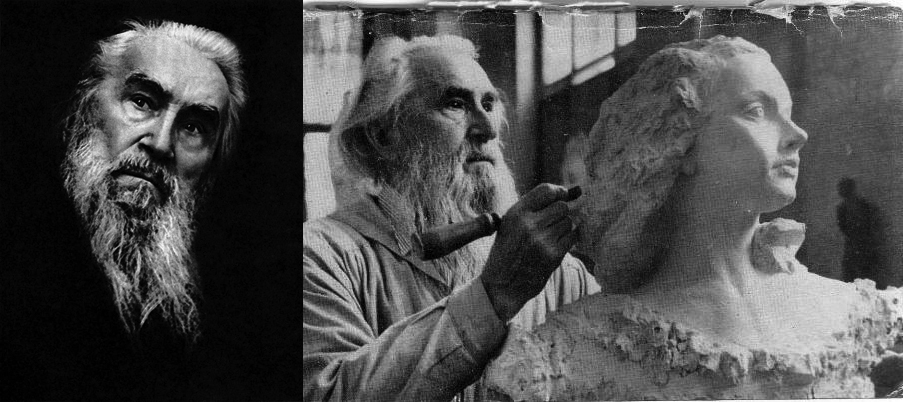

Sergey Timofeyevich Konenkov

Not many sculptors are fond of working with wood. The Konenkov's wood processing approach, when he used the rare qualities atypical of this material – quirkiness, whimsicalness of its outline, calling to fantasize things created by nature, entering into a dialogue therewith, by perceiving it as a kind of co-author, to treat the wood as an "equal" person, to catch and finish the image created by nature, is found in a small plastic art extremely rare.

S. T. Konenkov The Girl, 1914. Wood, The Torso, 1913 Marble, The Winged, 1913 Wood

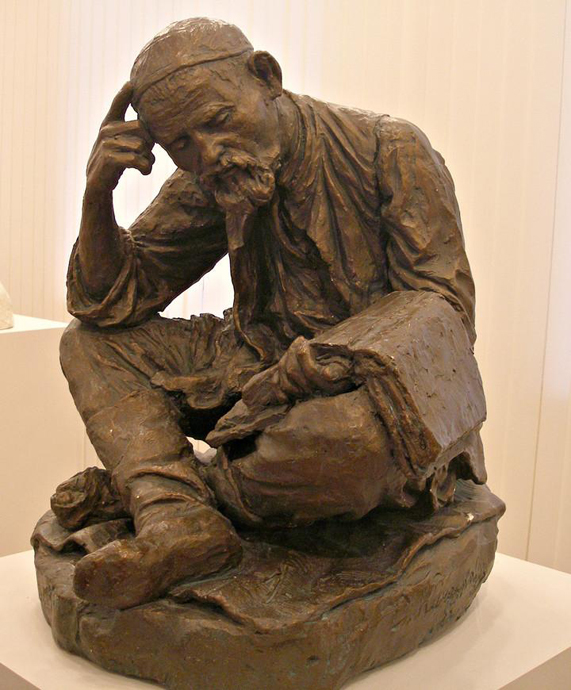

One of the earliest works by Konenkov – Reading Tatar (1895) – was created during the teachings of the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture.

S. T. Konenkov Reading Tatar, 1895.

Portrait of F. M. Dostoevsky is the most significant work, awarded with the Grand Prix at Brussels in 1958. The image of Dostoevsky did not leave the sculptor during his life abroad. "I thought of Dostoevsky as a powerful thinker who was next to me. Who else, like him, could understood and hated evil, who else, like him, could feel human suffering", Sergey Timofeyevich recalled.

S. T. Konenkov Fyodor Dostoyevsky's Penal Servitude. 1933 Museum of sculpture of S. T. Konenkov, Smolensk

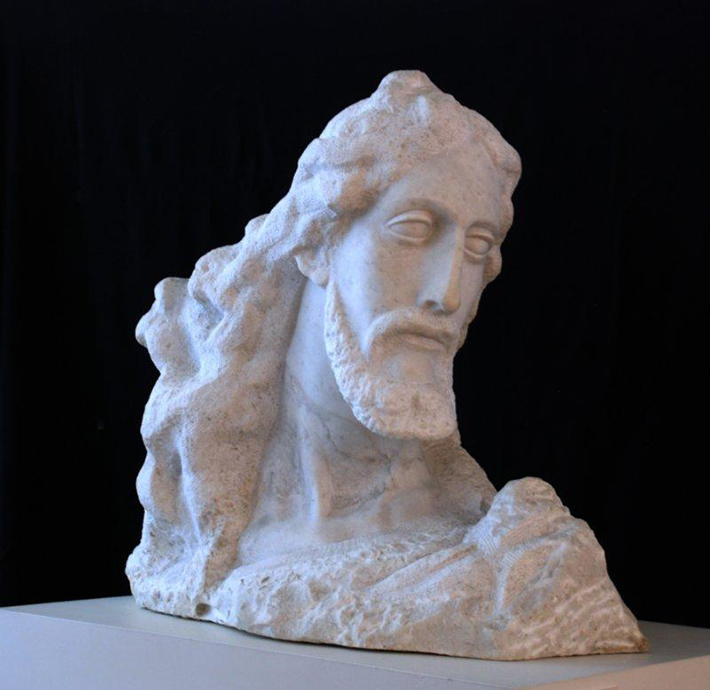

Christian theme is one of the leading in the works by Sergey Timofeyevich. Christianity attracted him as a person and as an artist. Jesus Christ is one of the master's most beautiful creations. Sergey Timofeyevich created the sculpture in 1933, when he lived and worked in America. He was already mature, established artist who had accumulated enormous human and creative potential. He had something to tell people about this image, which worried him so much for all his life.

S. T. Konenkov "Christ", 1933. Marble

There's a great mystery in the person thereof. Just take a good look – his eyes have no pupils. Why? The sculptor himself did not give an answer to this question, but, as an artist, he had the right to depict Christ in such way. As you look into the spiritualized face of Christ, try to discover this mystery – the mystery of his eyes.

S. T. Konenkov "Christ", 1933. Marble

Sergei Timofeyevich did not stop his creative work until old age, and was always full of creative plans, interesting ideas. The Russia's first woman to rise to fame as a sculptor was Anna Semenovna Golubkina. Golubkina's becoming famous was not a miracle. The miracle was that she managed to become a sculptor at all. As in the 19th century, it was difficult for a woman to master a profession.

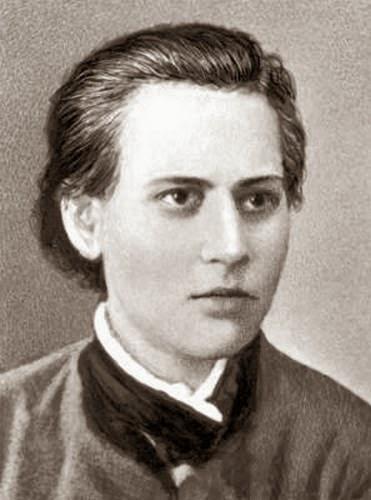

A. S. Golubkina (1864-1927)

Anna Golubkina had no education, even the primary one. Anna was twenty-five years old, when she came to Moscow and entered the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. "In the workshop, between the ancient casts, she was strict and majestic, she looked like Sibyl, mythical ancient prophetess," her messmate S. T. Konenkov recalled.

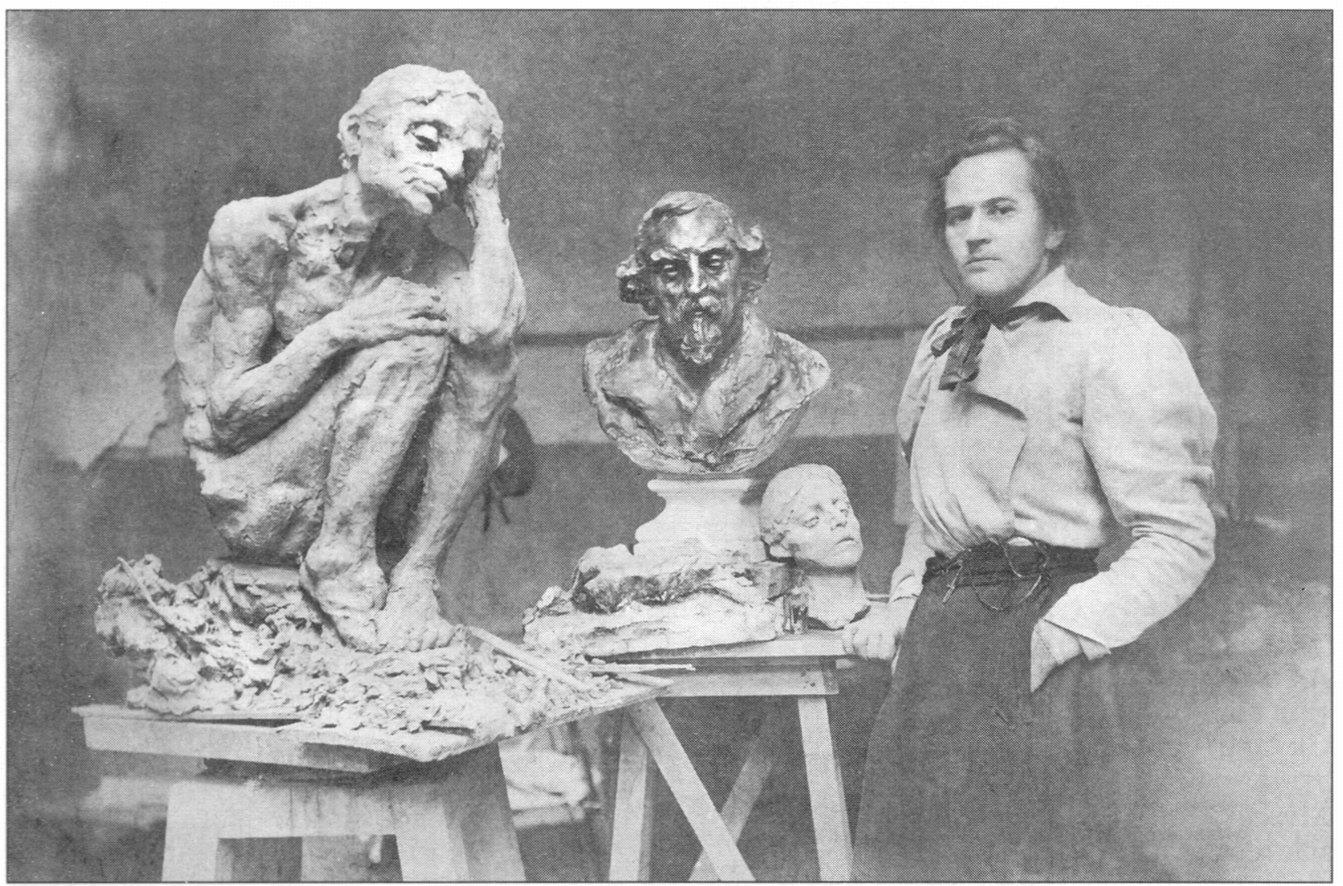

A. S. Golubkina

Identity and strength of Golubkina's talent yet in the years of study attracted everyone's attention to her. Later she moved to the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts. A. V. Beklemishev, was among those professors, who played a special role in the life of Anna Golubkina. In 1895, Anna left for Paris to continue her education. She goes to the Académie Colarossi, but very soon, she realizes that there dominates salon-academic direction, the same as in St. Petersburg, completely alien to her in spirit.

A. S. Golubkina and a group of artists, Paris. Photograph. 1895

The 1895 was a very difficult year for the young sculptor. Anna was tormented by creative dissatisfaction, doubts about the loyalty to the chosen path, feelings not faded for Beklemishev, which leads her to a nervous disease. Artist Elizabeth Kruglikova, who also lived in Paris, takes Anna to Moscow. Having restored peace of mind in the psychiatric clinic of the famous Korsakov, Anna returns to Paris in 1897 and finally finds someone from whom she should learn. The great Auguste Rodin saw her works and asked her to do the same under his leadership. Many years later, remembering a year of work with the master, Anna wrote to him: "You told me what I felt, and you gave me the opportunity to be free." In 1898, she presented the sculpture of the "Old Age" at the Paris Salon (the most prestigious art competition of that time). For this statue, the same aged model was posing as for Rodin's She Who Was The Helmet Maker's Once-Beautiful Wife (1885).

A. S. Golubkina in Paris, next to the sculpture of Old Age. Photograph. 1898

Golubkina interpreted the teacher in her own way. And did it successfully. She was awarded with a bronze medal and praised in the press. When she returned to Russia next year, they already talked about her. In 1901, she received an order for sculptural decoration of the main entrance of the Moscow Art Theater. High relief of Wave – a rebellious spirit, struggling with the elements – has still adorned the entrance to the old building of the Moscow Art Theater.

Golubkina A. S. the Wave high relief, 1901 Plaster cast, 2.5 x 2.7 m

She visited Paris in 1902 once again. She also visited London and Berlin, by getting acquainted with the masterpieces of world art.

A. S. Golubkina, The Last Supper, 1911

When the World War I started, her first solo exhibition was held at the Museum of Fine Arts. Golubkina was already fifty. The audience at the exhibition was bursting, the profit from the tickets was huge. The critics wrote, "Never before has Russian sculpture tugged at viewer's heart-strings so deeply, as in this exhibition, arranged in the days of great trials."

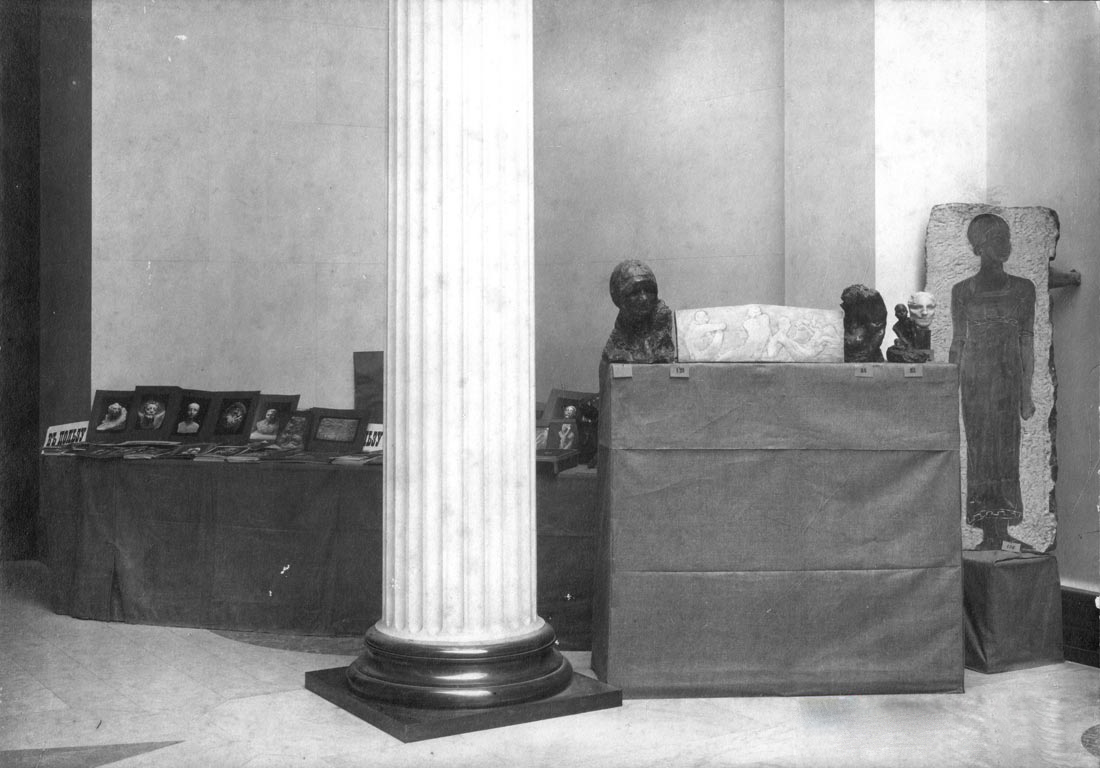

A. S. Golubkina, sole exhibition, 1914

In the 1920s, Golubkina earned her living by teaching. Her health was weak — acute gastric ulcer, which had to be operated. Golubkina's last work – The Portrait of L. N. Tolstoy – suddenly was the indirect cause of her death. In her youth, Anna Semenovna once met with the "great elder" and, according to an eyewitness, she seriously argued with him about something. The impression of this meeting remained so strong that many years later she refused to use his photographs and "made a portrait from the idea and her own memories: Tolstoy as the sea... but his eyes are like those of hunted wolf."

On the left: A. S. Golubkina, The Portrait of V. G. Chertkov, 1926. Wood. Tolstoy State Museum.

On the right: A. S. Golubkina, The Portrait of L. N. Tolstoy, 1927. Tinted plaster. Memorial Museum-Workshop of Sculptor A. S. Golubkina.

The block, glued together from several pieces of wood, was massive and heavy, and Anna Semenovna should have not moved it in any case after the operation undergone in 1922. But she forgot about age and the disease. When two of her students unsuccessfully fought with wooden edifice, she moved them with shoulder and forcefully pushed the stubborn tree. Soon after, she felt bad and hurried to her sister in Zaraysk. The departure was a fatal mistake. Professor A. Martynov, who had been treating the artist for many years, said that an immediate operation would certainly save her... Portrait of Tolstoy remained forever a plaster one – sculptor did not have time to transfer the portrait into wood. Anna Semenovna was very emotional and vulnerable, but this did not prevent her from defending her principles and creating her art at a time when everyone else was trying to keep up with fashion.

The Acquisition. Lobortas House

Photo by Vladislav Filin.